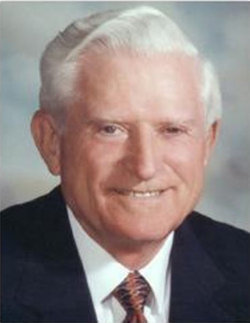

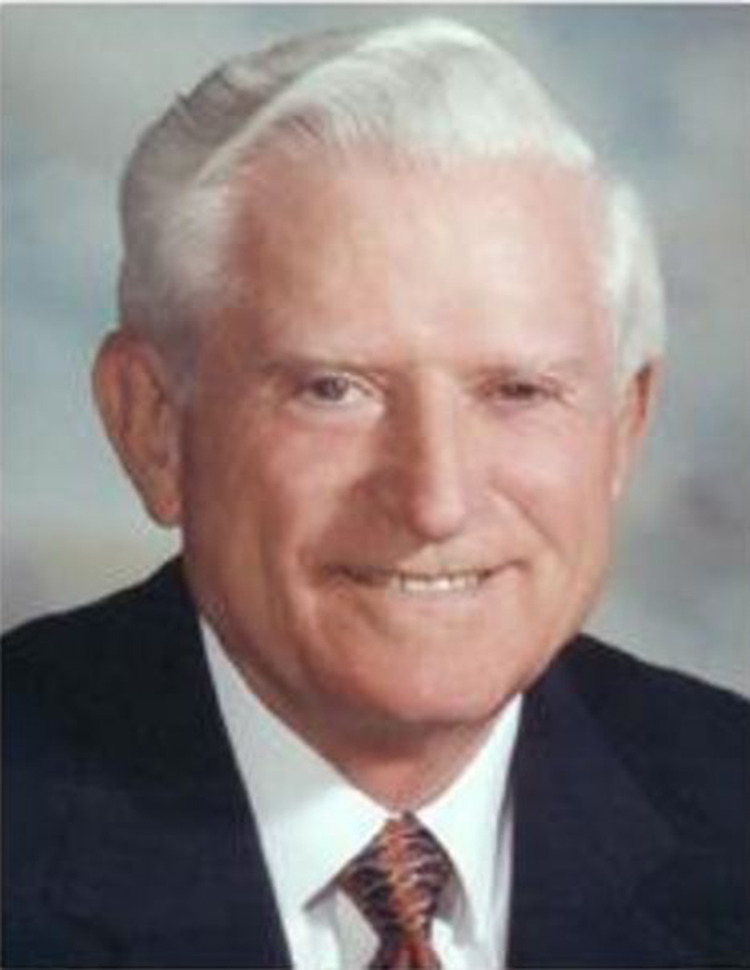

Name: Gene Myron Amdahl

Event Type: Baptism

Birth Date: 16 Nov 1922

Baptism Date: 25 Dec 1922

Baptism Place: Roslyn, South Dakota

Father: Anton Amdahl

Mother: Ingeborg Brendell [Brendsel]

Church Name: Fron Lutheran

Church Location: Roslyn, South Dakota

Marriage Date: 23 Jun 1946

Marriage Place: Moody, South Dakota, USA

Predeceased by brothers Alton Jefferson Amdahl 1918-2004, Orin B Amdahl 1920-1945 and sister Evelyn Ingeborg Amdahl (Felix) Olson 1919-2000,

"Gene Myron Amdahl, 92, went to be with his Lord on November 10, 2015 at the Vi Skilled Nursing Center in Palo Alto after a long struggle with Alzheimer's, finally succumbing to pneumonia.

Gene was born in Flandreau, SD on November 16, 1922, and went on to become a legend in the computer industry. His accomplishments are widely published and too numerous to mention.

Gene is survived by his loving wife of 69 years, his children, hs grandchildren and his brother. Gene loved his family, taking great pride in their achievements and valuing them as individuals.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Alzheimer's Association (www.alz.org), a non-profit organization."

SOURCE: "Celebrating the Life of Gene Amdahl", Wednesday, November 25, 2015, Menlo Park Presbyterian Church

"Gene Amdahl, IBM Designer Who Founded Rival, Dies at 92

Gene Amdahl, who helped IBM usher in general-purpose computers in the 1960s and challenged the company's dominance a decade later with his eponymous machines, has died. He was 92.

He died on Nov. 10 at Vi at Palo Alto, a continuing care retirement community in Palo Alto, California, his wife said in a telephone interview. The cause was pneumonia, and he had Alzheimer's disease for about five years.

Amdahl shepherded the design of the IBM Series/360, the first computer system not built for a specific purpose and one that offered modularity, interoperability -- software made for one machine could run on another -- and the use of cheaper third-party peripherals. Announced in 1964, it made IBM the king of mainframes, closet-sized data crunchers, by expanding the market to everyday businesses such as airlines and carmakers from a user base limited to government offices and universities.

"That architecture has endured for 50 years," Mike Chuba, an analyst who has followed the industry for more than three decades at Stamford, Connecticut-based Gartner Inc., said in a 2014 telephone interview. "Most credit-card transactions will go through a mainframe at some point."

Amdahl improved that design and took on Big Blue by focusing on high-end customers. His machines, typically colored red, were essentially IBM clones that could be interchanged with the bigger company's products. A price war followed and Amdahl Corp.'s founder left in 1979, about four years after selling its first device.

New Era

Bigger changes were near for the industry. International Business Machines Corp., based in Armonk, New York, introduced its personal computer in 1981.

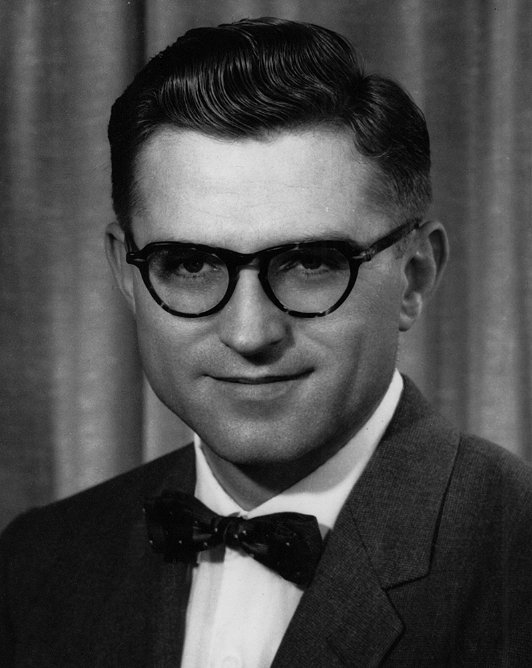

Gene Myron Amdahl was born on Nov. 16, 1922, in Flandreau, South Dakota. He was the fourth of five children of Anton Amdahl and the former Ingeborg Brendsel, both offspring of Scandinavian homesteaders. The future computer pioneer didn't have electricity at home until he was in high school, he said, according to an oral history published by the University of Minnesota.

He started college at what is now South Dakota State University in 1941, the year Pearl Harbor was bombed. In 1944, he joined the U.S. Navy, where he received training in electronics. Discharged from the military two years later, he married his wife, who grew up four miles from his childhood home. He returned to South Dakota State in 1947 and graduated the following year with a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering physics.

Doctoral Thesis

A graduate program in theoretical physics brought Amdahl to the University of Wisconsin at Madison in 1948. He started thinking about building one of the first digital computers for large-scale calculations after he found a desk calculator and slide rule inadequate to solve a problem he was tackling that involved nuclear particles.

Amdahl's Ph.D. thesis, which laid out the design of one of the first computers, was too complex to be graded at the school and was sent for evaluation to the U.S. Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. In 1952, he received a doctorate, which also brought a job offer from IBM.

Working at IBM's Poughkeepsie, New York, office, Amdahl was the main designer for the IBM 704, a mainframe built for engineering and scientific work. He left in 1955, only to be wooed to return for a rare second stint in 1960.

IBM spent $5 billion over four years on the 360 system at a time when it had $2.5 billion in annual revenue. Designed with new circuitry and memory management, it was cheaper to make and replaced IBM's entire product line. Amdahl managed the architecture of the 360, which became the company's most profitable product.

Amdahl's Law

In 1965, Amdahl was made an IBM Fellow, free to pursue his own projects. Four years later, he laid out the physical limitations of speeding-up computers that came to be known as Amdahl's law.

He left IBM again in 1970 after disagreements about a plan he devised to build a supercomputer; IBM said it wouldn't be profitable.

With funding help from Japan's Fujitsu Ltd., he formed Amdahl Corp., located in Sunnyvale, California, whose first product was more powerful and smaller than IBM's devices. The Amdahl computer, first sold in 1975, was cooled by air, not by water as was the norm then, and used a bigger-than-usual chip, which made its design less complex. The company also benefited from IBM's antitrust agreement with the U.S. government that required the computer maker to license some of its mainframe technology.

Price War

Orders rolled in from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ford Motor Co. and American Telephone & Telegraph Co. Soon Amdahl's company gained 22 percent of the high-end mainframe market, he said. IBM responded with a faster machine and cut prices by 30 percent.

"I figured they were mowing grass at the ground level," Amdahl said in a 2011 Computer History Museum video.

In 1979, he left the company. About two decades later, Fujitsu paid about $850 million for the 58 percent of Amdahl Corp. that it didn't already own.

Amdahl continued his quest to challenge IBM by designing advanced supercomputers, forming Trilogy Systems Corp., in Cupertino, California. The challenge was too costly, however, and Amdahl gave up on supercomputers in 1984, four years after founding the company with his son. The company shifted its focus to making the giant silicon wafers for the most powerful machines."

SOURCE: Bloomberg News, by Vivek Shankar

In computer architecture, Amdahl's law (or Amdahl's argument[1]) gives the theoretical speedup in latency of the execution of a task at fixed workload that can be expected of a system whose resources are improved. It is named after computer scientist Gene Amdahl, and was presented at the AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference in 1967.

"Gene Amdahl, Pioneer of Mainframe Computing, Dies at 92

Gene Amdahl, a trailblazer in the design of IBM's mainframe computers, which became the central nervous system for businesses large and small throughout the world, died on Tuesday at a nursing home in Palo Alto, Calif. He was 92.

His wife, Marian, said the cause was pneumonia. He had been treated for Alzheimer's disease for about five years, she said.

Dr. Amdahl rose from South Dakota farm country, where he attended a one-room school without electricity, to become the epitome of a generation of computer pioneers who combined intellectual brilliance, managerial skill and entrepreneurial vigor to fuel the early growth of the industry.

As a young computer scientist at International Business Machines Corporation in the early 1960s, he played a crucial role in the development of the System/360 series, the most successful line of mainframe computers in IBM's history. Its architecture influenced computer design for years to come.

The 360 series was not one computer but a family of compatible machines. Computers in the series used processors of different speeds and power, yet all understood a common language.

This allowed customers to purchase a smaller system knowing they could migrate to a larger, more powerful machine if their needs grew, without reprogramming the application software. IBM's current mainframes can still run some System/360 applications.

The system was announced at IBM's annual shareholders meeting on April 7, 1964, in Endicott, N.Y., a village near Binghamton where the company had opened a facility early in the 20th century.

At the meeting, Thomas J. Watson Jr., then chairman and chief executive, singled out Dr. Amdahl as the "father" of the new computer. "I remember it very clearly," Marian Amdahl said in an interview. "Gene was so proud of that."

Michael J. Flynn, a computer scientist at Stanford University and former colleague of Dr. Amdahl's at IBM, said the 360 series "set the design philosophy for computers for the next 50 years, and to this day it's still out there, which is incredible."

"This same instruction set," he added, "is still bringing in billions of dollars for IBM."

Dr. Amdahl is remembered at IBM as an intellectual leader who could get different strong-minded groups to reach agreement on technical issues.

"By sheer intellectual force, plus some argument and banging on the table, he maintained architectural consistency across six engineering teams," said Frederick P. Brooks Jr., a computer scientist who was the project manager of the System/360 and is now at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Dr. Amdahl's business instincts and ambitions manifested themselves in 1970, when he left IBM to build a company to rival it. At the time, the market for mainframe computers belonged almost exclusively to IBM.

With funding from Fujitsu, he formed the Amdahl Corporation, setting up offices in Sunnyvale, Calif.

"We took about three weeks to do an analysis of the formidable task of competing head-on with IBM," Dr. Amdahl said in a 2007 interview with Solid-State Circuits Society News.

His idea was to build machines compatible with hardware and software for the System/370, the successor to the System/360. He pointedly named it the 470 series, and in 1975 his company shipped the first of the machines. It proved faster and less expensive than IBM's comparable computers.

By purchasing an Amdahl computer and so-called plug-compatible peripheral devices from third-party manufacturers, customers could now run System/370 programs without buying IBM hardware.

The Amdahl Corporation was not the first to make IBM-compatible computers, but it managed to compete successfully against IBM where large companies like RCA and General Electric had failed.

Amdahl also benefited from antitrust settlements between IBM and the Justice Department, which required IBM to make its mainframe software available to competitors.

By 1979, the year Dr. Amdahl left the company to start another venture, Amdahl had more than $200 million in annual revenue and 22 percent of the mainframe market.

(Fujitsu bought the remaining interest in Amdahl in 1997 and made it a wholly owned subsidiary. It has since been dissolved as a stand-alone entity.)

Dr. Amdahl also formulated what became known as Amdahl's Law, which is used in parallel computing to predict the theoretical maximum improvement in speed using multiple processors.

Gene Myron Amdahl was born on Nov. 16, 1922, in Flandreau, S.D., to parents of Norwegian and Swedish descent. He grew up on a farm and attended a one-room school through the eighth grade. Rural electrification did not reach his town until he was a freshman in high school.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, he tried to join the military, but the Selective Service turned him down, deeming his farming skills more important. "They'd drafted so many of the youth that there weren't enough people to harvest," he told an interviewer in 1989.

Dr. Amdahl finally joined the service, the Navy, in 1944, and taught radar at naval training centers around the country. In 1946 he married Marian Quissell, who grew up on a farm four miles from his.

He received his bachelor's degree in 1948 from South Dakota State University, in Brookings, where his wife worked as a secretary. She had dropped out of Augustana College in Sioux Falls, S.D., after her freshman year to go to work to help pay for her husband's education. In 1952 he received his doctorate in theoretical physics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

It was in graduate school that his interest in the nascent field of digital computers took root. For his Ph.D. thesis, he drafted a design for what became known as the Wisconsin Integrally Synchronized Computer, or W.I.S.C., an early digital computer.

Dr. Amdahl was recruited by IBM after a branch manager in Madison visited him at the university and offered him a job straight out of graduate school.

After the success of the System/360 project, Dr. Amdahl moved to California in 1964, weary of what he described as "the time and politicking demands" at IBM's corporate headquarters in Armonk, N.Y. In California, he managed an IBM engineering laboratory for six years before starting Amdahl in Sunnyvale, in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Dr. Amdahl also encountered both technical and business disappointments. One was Trilogy Systems, which he created after leaving Amdahl in 1979. Trilogy set out to build an integrated chip that would allow mainframe manufacturers to build computers at lower costs. It raised more than $200 million in public and private financing. Yet the chip development ultimately failed.

In 1987 Dr. Amdahl started the Andor Corporation, hoping to compete in the midsize mainframe market using improved manufacturing techniques. But the company encountered production problems, which, together with strong competition, led it to bankruptcy in 1995.

Besides his wife, Dr. Amdahl is survived by two daughters, a son, who was vice chairman of Trilogy; a brother, and five grandchildren.

Despite his business failures later in life, Mr. Amdahl's reputation for technical brilliance endured. Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., compared him to two of the industry's greatest computer architects.

"He's always been right up there with Seymour Cray or Steve Wozniak," Mr. Spicer said, "with real cachet in the technical community."

SOURCE: The New York Times, November 15, 2015, page B1,

By KATIE HAFNER

Name: Gene Myron Amdahl

Event Type: Baptism

Birth Date: 16 Nov 1922

Baptism Date: 25 Dec 1922

Baptism Place: Roslyn, South Dakota

Father: Anton Amdahl

Mother: Ingeborg Brendell [Brendsel]

Church Name: Fron Lutheran

Church Location: Roslyn, South Dakota

Marriage Date: 23 Jun 1946

Marriage Place: Moody, South Dakota, USA

Predeceased by brothers Alton Jefferson Amdahl 1918-2004, Orin B Amdahl 1920-1945 and sister Evelyn Ingeborg Amdahl (Felix) Olson 1919-2000,

"Gene Myron Amdahl, 92, went to be with his Lord on November 10, 2015 at the Vi Skilled Nursing Center in Palo Alto after a long struggle with Alzheimer's, finally succumbing to pneumonia.

Gene was born in Flandreau, SD on November 16, 1922, and went on to become a legend in the computer industry. His accomplishments are widely published and too numerous to mention.

Gene is survived by his loving wife of 69 years, his children, hs grandchildren and his brother. Gene loved his family, taking great pride in their achievements and valuing them as individuals.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Alzheimer's Association (www.alz.org), a non-profit organization."

SOURCE: "Celebrating the Life of Gene Amdahl", Wednesday, November 25, 2015, Menlo Park Presbyterian Church

"Gene Amdahl, IBM Designer Who Founded Rival, Dies at 92

Gene Amdahl, who helped IBM usher in general-purpose computers in the 1960s and challenged the company's dominance a decade later with his eponymous machines, has died. He was 92.

He died on Nov. 10 at Vi at Palo Alto, a continuing care retirement community in Palo Alto, California, his wife said in a telephone interview. The cause was pneumonia, and he had Alzheimer's disease for about five years.

Amdahl shepherded the design of the IBM Series/360, the first computer system not built for a specific purpose and one that offered modularity, interoperability -- software made for one machine could run on another -- and the use of cheaper third-party peripherals. Announced in 1964, it made IBM the king of mainframes, closet-sized data crunchers, by expanding the market to everyday businesses such as airlines and carmakers from a user base limited to government offices and universities.

"That architecture has endured for 50 years," Mike Chuba, an analyst who has followed the industry for more than three decades at Stamford, Connecticut-based Gartner Inc., said in a 2014 telephone interview. "Most credit-card transactions will go through a mainframe at some point."

Amdahl improved that design and took on Big Blue by focusing on high-end customers. His machines, typically colored red, were essentially IBM clones that could be interchanged with the bigger company's products. A price war followed and Amdahl Corp.'s founder left in 1979, about four years after selling its first device.

New Era

Bigger changes were near for the industry. International Business Machines Corp., based in Armonk, New York, introduced its personal computer in 1981.

Gene Myron Amdahl was born on Nov. 16, 1922, in Flandreau, South Dakota. He was the fourth of five children of Anton Amdahl and the former Ingeborg Brendsel, both offspring of Scandinavian homesteaders. The future computer pioneer didn't have electricity at home until he was in high school, he said, according to an oral history published by the University of Minnesota.

He started college at what is now South Dakota State University in 1941, the year Pearl Harbor was bombed. In 1944, he joined the U.S. Navy, where he received training in electronics. Discharged from the military two years later, he married his wife, who grew up four miles from his childhood home. He returned to South Dakota State in 1947 and graduated the following year with a Bachelor of Science degree in engineering physics.

Doctoral Thesis

A graduate program in theoretical physics brought Amdahl to the University of Wisconsin at Madison in 1948. He started thinking about building one of the first digital computers for large-scale calculations after he found a desk calculator and slide rule inadequate to solve a problem he was tackling that involved nuclear particles.

Amdahl's Ph.D. thesis, which laid out the design of one of the first computers, was too complex to be graded at the school and was sent for evaluation to the U.S. Army's Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. In 1952, he received a doctorate, which also brought a job offer from IBM.

Working at IBM's Poughkeepsie, New York, office, Amdahl was the main designer for the IBM 704, a mainframe built for engineering and scientific work. He left in 1955, only to be wooed to return for a rare second stint in 1960.

IBM spent $5 billion over four years on the 360 system at a time when it had $2.5 billion in annual revenue. Designed with new circuitry and memory management, it was cheaper to make and replaced IBM's entire product line. Amdahl managed the architecture of the 360, which became the company's most profitable product.

Amdahl's Law

In 1965, Amdahl was made an IBM Fellow, free to pursue his own projects. Four years later, he laid out the physical limitations of speeding-up computers that came to be known as Amdahl's law.

He left IBM again in 1970 after disagreements about a plan he devised to build a supercomputer; IBM said it wouldn't be profitable.

With funding help from Japan's Fujitsu Ltd., he formed Amdahl Corp., located in Sunnyvale, California, whose first product was more powerful and smaller than IBM's devices. The Amdahl computer, first sold in 1975, was cooled by air, not by water as was the norm then, and used a bigger-than-usual chip, which made its design less complex. The company also benefited from IBM's antitrust agreement with the U.S. government that required the computer maker to license some of its mainframe technology.

Price War

Orders rolled in from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Ford Motor Co. and American Telephone & Telegraph Co. Soon Amdahl's company gained 22 percent of the high-end mainframe market, he said. IBM responded with a faster machine and cut prices by 30 percent.

"I figured they were mowing grass at the ground level," Amdahl said in a 2011 Computer History Museum video.

In 1979, he left the company. About two decades later, Fujitsu paid about $850 million for the 58 percent of Amdahl Corp. that it didn't already own.

Amdahl continued his quest to challenge IBM by designing advanced supercomputers, forming Trilogy Systems Corp., in Cupertino, California. The challenge was too costly, however, and Amdahl gave up on supercomputers in 1984, four years after founding the company with his son. The company shifted its focus to making the giant silicon wafers for the most powerful machines."

SOURCE: Bloomberg News, by Vivek Shankar

In computer architecture, Amdahl's law (or Amdahl's argument[1]) gives the theoretical speedup in latency of the execution of a task at fixed workload that can be expected of a system whose resources are improved. It is named after computer scientist Gene Amdahl, and was presented at the AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference in 1967.

"Gene Amdahl, Pioneer of Mainframe Computing, Dies at 92

Gene Amdahl, a trailblazer in the design of IBM's mainframe computers, which became the central nervous system for businesses large and small throughout the world, died on Tuesday at a nursing home in Palo Alto, Calif. He was 92.

His wife, Marian, said the cause was pneumonia. He had been treated for Alzheimer's disease for about five years, she said.

Dr. Amdahl rose from South Dakota farm country, where he attended a one-room school without electricity, to become the epitome of a generation of computer pioneers who combined intellectual brilliance, managerial skill and entrepreneurial vigor to fuel the early growth of the industry.

As a young computer scientist at International Business Machines Corporation in the early 1960s, he played a crucial role in the development of the System/360 series, the most successful line of mainframe computers in IBM's history. Its architecture influenced computer design for years to come.

The 360 series was not one computer but a family of compatible machines. Computers in the series used processors of different speeds and power, yet all understood a common language.

This allowed customers to purchase a smaller system knowing they could migrate to a larger, more powerful machine if their needs grew, without reprogramming the application software. IBM's current mainframes can still run some System/360 applications.

The system was announced at IBM's annual shareholders meeting on April 7, 1964, in Endicott, N.Y., a village near Binghamton where the company had opened a facility early in the 20th century.

At the meeting, Thomas J. Watson Jr., then chairman and chief executive, singled out Dr. Amdahl as the "father" of the new computer. "I remember it very clearly," Marian Amdahl said in an interview. "Gene was so proud of that."

Michael J. Flynn, a computer scientist at Stanford University and former colleague of Dr. Amdahl's at IBM, said the 360 series "set the design philosophy for computers for the next 50 years, and to this day it's still out there, which is incredible."

"This same instruction set," he added, "is still bringing in billions of dollars for IBM."

Dr. Amdahl is remembered at IBM as an intellectual leader who could get different strong-minded groups to reach agreement on technical issues.

"By sheer intellectual force, plus some argument and banging on the table, he maintained architectural consistency across six engineering teams," said Frederick P. Brooks Jr., a computer scientist who was the project manager of the System/360 and is now at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Dr. Amdahl's business instincts and ambitions manifested themselves in 1970, when he left IBM to build a company to rival it. At the time, the market for mainframe computers belonged almost exclusively to IBM.

With funding from Fujitsu, he formed the Amdahl Corporation, setting up offices in Sunnyvale, Calif.

"We took about three weeks to do an analysis of the formidable task of competing head-on with IBM," Dr. Amdahl said in a 2007 interview with Solid-State Circuits Society News.

His idea was to build machines compatible with hardware and software for the System/370, the successor to the System/360. He pointedly named it the 470 series, and in 1975 his company shipped the first of the machines. It proved faster and less expensive than IBM's comparable computers.

By purchasing an Amdahl computer and so-called plug-compatible peripheral devices from third-party manufacturers, customers could now run System/370 programs without buying IBM hardware.

The Amdahl Corporation was not the first to make IBM-compatible computers, but it managed to compete successfully against IBM where large companies like RCA and General Electric had failed.

Amdahl also benefited from antitrust settlements between IBM and the Justice Department, which required IBM to make its mainframe software available to competitors.

By 1979, the year Dr. Amdahl left the company to start another venture, Amdahl had more than $200 million in annual revenue and 22 percent of the mainframe market.

(Fujitsu bought the remaining interest in Amdahl in 1997 and made it a wholly owned subsidiary. It has since been dissolved as a stand-alone entity.)

Dr. Amdahl also formulated what became known as Amdahl's Law, which is used in parallel computing to predict the theoretical maximum improvement in speed using multiple processors.

Gene Myron Amdahl was born on Nov. 16, 1922, in Flandreau, S.D., to parents of Norwegian and Swedish descent. He grew up on a farm and attended a one-room school through the eighth grade. Rural electrification did not reach his town until he was a freshman in high school.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, he tried to join the military, but the Selective Service turned him down, deeming his farming skills more important. "They'd drafted so many of the youth that there weren't enough people to harvest," he told an interviewer in 1989.

Dr. Amdahl finally joined the service, the Navy, in 1944, and taught radar at naval training centers around the country. In 1946 he married Marian Quissell, who grew up on a farm four miles from his.

He received his bachelor's degree in 1948 from South Dakota State University, in Brookings, where his wife worked as a secretary. She had dropped out of Augustana College in Sioux Falls, S.D., after her freshman year to go to work to help pay for her husband's education. In 1952 he received his doctorate in theoretical physics from the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

It was in graduate school that his interest in the nascent field of digital computers took root. For his Ph.D. thesis, he drafted a design for what became known as the Wisconsin Integrally Synchronized Computer, or W.I.S.C., an early digital computer.

Dr. Amdahl was recruited by IBM after a branch manager in Madison visited him at the university and offered him a job straight out of graduate school.

After the success of the System/360 project, Dr. Amdahl moved to California in 1964, weary of what he described as "the time and politicking demands" at IBM's corporate headquarters in Armonk, N.Y. In California, he managed an IBM engineering laboratory for six years before starting Amdahl in Sunnyvale, in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Dr. Amdahl also encountered both technical and business disappointments. One was Trilogy Systems, which he created after leaving Amdahl in 1979. Trilogy set out to build an integrated chip that would allow mainframe manufacturers to build computers at lower costs. It raised more than $200 million in public and private financing. Yet the chip development ultimately failed.

In 1987 Dr. Amdahl started the Andor Corporation, hoping to compete in the midsize mainframe market using improved manufacturing techniques. But the company encountered production problems, which, together with strong competition, led it to bankruptcy in 1995.

Besides his wife, Dr. Amdahl is survived by two daughters, a son, who was vice chairman of Trilogy; a brother, and five grandchildren.

Despite his business failures later in life, Mr. Amdahl's reputation for technical brilliance endured. Dag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., compared him to two of the industry's greatest computer architects.

"He's always been right up there with Seymour Cray or Steve Wozniak," Mr. Spicer said, "with real cachet in the technical community."

SOURCE: The New York Times, November 15, 2015, page B1,

By KATIE HAFNER

Family Members

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement

Advertisement