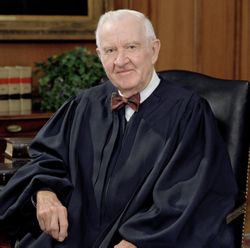

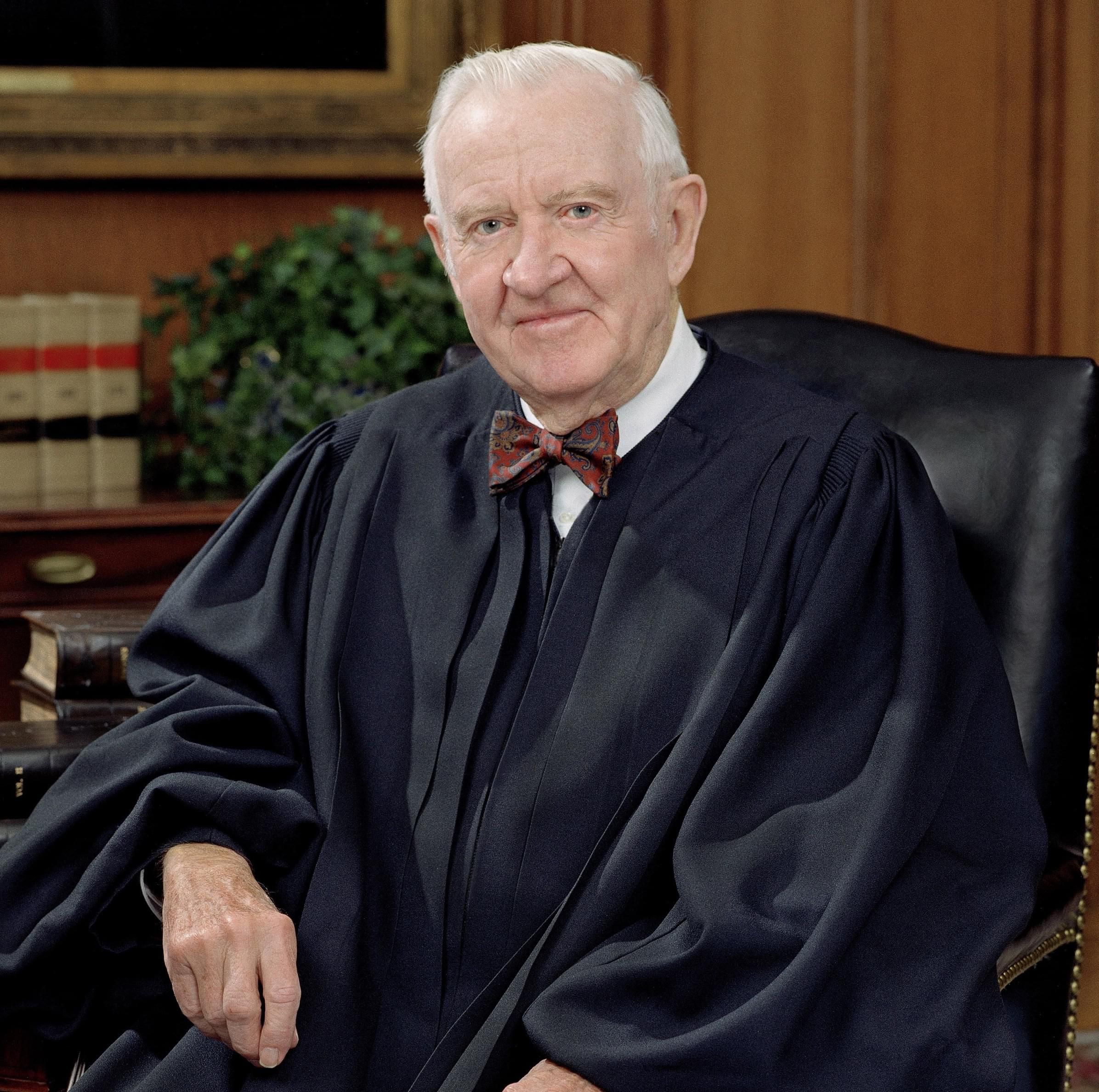

In 1975, President Gerald Ford appointed him to the United States Supreme Court. The nomination drew instant praise from Democrats and Republicans alike, and Stevens, wearing his trademark bow tie, was confirmed in a remarkable three weeks. Ford had assigned his Attorney General, Edward Levi, a man chosen for his lack of political ties, to do the screening, and Levi, the onetime Dean of the University of Chicago Law School, quickly fixed his eye on Stevens, a lifelong Republican with no record of political or judicial activism.

Once on the court, Stevens quickly earned a reputation for quality work and independence. Over time, he was seen as an increasingly respected and influential justice, a man beloved by his colleagues for his decency, his unassuming nature, and his tough inner core. In his first decade, he was viewed as a center-right justice, but as the composition of the court grew more and more conservative, he found himself referred to as the court's most liberal member.

Over the years, he wrote over 400 majority opinions for the court on almost every issue: property rights, immigration, abortion, obscenity, school prayer, campaign-finance reform, term limits, and the relationship between the federal and state governments. The decisions Stevens will likely be remembered for most, though, are those he authored on national security and presidential power.

Stevens wrote the court's 5-to-3 decision renouncing President George W. Bush's assertion of unilateral executive power in setting up war crimes tribunals at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In 2004, he authored the court's 6-to-3 decision allowing the Guantanamo detainees to challenge their detentions in the United States Courts. Both had profound implications for the limits of presidential power. He also wrote the opinion for a unanimous court in Clinton v. Jones, the decision refusing to postpone Paula Jones' sexual harassment lawsuit against President Bill Clinton. In summarizing the decision from the bench in 1997, he dismissed the notion that the suit would burden the presidency.

While he wrote some of the court's most complex and important decisions, often bringing together under one legal tent justices one might not expect to agree, he also dissented from the court's rulings more frequently than any other justice during his long tenure on the bench. When the court struck down a Texas law that punished burning the American flag, Stevens, a Navy veteran and winner of the Bronze Star, objected, declaring that "the value of the of the flag as a symbol cannot be measured." When the court revived the doctrine of states' rights, he dissented. In 1997, when the court majority ruled that a key section of the Brady gun-control law unconstitutionally conscripted local law enforcement to conduct background checks of gun buyers, he took the unusual step of announcing his dissent from the bench. His angriest dissent came, without doubt, in 2000, in the case of Bush v. Gore, which effectively ended the presidential race in favor of George W. Bush. "Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year's presidential election," he wrote, "the identity of the loser is clear. It is the nation's confidence in the judge as impartial guardian of the rule of law."

In 1992, he played a pivotal role in the court's reconsideration of its landmark 1973 abortion ruling, Roe v. Wade. The court was split into three separate factions: four justices to reverse Roe outright, three to uphold its core but allow more regulation by the states, and two, including Stevens and Harry Blackmun, to uphold Roe entirely. Upon receiving the draft of the three middle-ground justices, Stevens suggested a reorganization of their opinion so that he and Blackmun, the author of Roe, could join most of it. That way, he noted, there would be a single opinion that was supported by a court majority of five. The three quickly agreed, and the opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey became the new law of the land.

In his 2010 National Public Radio interview, Stevens said that in all of his years on the court, he really had just one regret: his 1976 vote to revive the death penalty by upholding a Texas death penalty statute. He said that, at the time, the court had adopted many rules to limit the death penalty to a narrow category of offenders and to prevent what he called "loading the dice" for the prosecution, but, over time, those limiting rules were abandoned. In his later years, he opposed most death sentences, winning rare but important victories, as when he wrote the court's opinion striking down capital punishment for the mentally retarded.

He maintained he was undecided about retiring, but in late June of 2010, his lengthy oral dissent in the campaign finance case was marred by verbal flubs. He was so distressed by his performance that he sought a complete checkup by his doctor. There was nothing wrong, but, not long thereafter, at age 90, he announced his retirement.

In the years afterward, he continued to be both physically and intellectually active, playing tennis and golf, and writing and speaking about the court and its work. When he thought the court in error, he gave critiques which were always pointed, literate, and respectful -- the very qualities that made him such a revered figure in the law.

In 1975, President Gerald Ford appointed him to the United States Supreme Court. The nomination drew instant praise from Democrats and Republicans alike, and Stevens, wearing his trademark bow tie, was confirmed in a remarkable three weeks. Ford had assigned his Attorney General, Edward Levi, a man chosen for his lack of political ties, to do the screening, and Levi, the onetime Dean of the University of Chicago Law School, quickly fixed his eye on Stevens, a lifelong Republican with no record of political or judicial activism.

Once on the court, Stevens quickly earned a reputation for quality work and independence. Over time, he was seen as an increasingly respected and influential justice, a man beloved by his colleagues for his decency, his unassuming nature, and his tough inner core. In his first decade, he was viewed as a center-right justice, but as the composition of the court grew more and more conservative, he found himself referred to as the court's most liberal member.

Over the years, he wrote over 400 majority opinions for the court on almost every issue: property rights, immigration, abortion, obscenity, school prayer, campaign-finance reform, term limits, and the relationship between the federal and state governments. The decisions Stevens will likely be remembered for most, though, are those he authored on national security and presidential power.

Stevens wrote the court's 5-to-3 decision renouncing President George W. Bush's assertion of unilateral executive power in setting up war crimes tribunals at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. In 2004, he authored the court's 6-to-3 decision allowing the Guantanamo detainees to challenge their detentions in the United States Courts. Both had profound implications for the limits of presidential power. He also wrote the opinion for a unanimous court in Clinton v. Jones, the decision refusing to postpone Paula Jones' sexual harassment lawsuit against President Bill Clinton. In summarizing the decision from the bench in 1997, he dismissed the notion that the suit would burden the presidency.

While he wrote some of the court's most complex and important decisions, often bringing together under one legal tent justices one might not expect to agree, he also dissented from the court's rulings more frequently than any other justice during his long tenure on the bench. When the court struck down a Texas law that punished burning the American flag, Stevens, a Navy veteran and winner of the Bronze Star, objected, declaring that "the value of the of the flag as a symbol cannot be measured." When the court revived the doctrine of states' rights, he dissented. In 1997, when the court majority ruled that a key section of the Brady gun-control law unconstitutionally conscripted local law enforcement to conduct background checks of gun buyers, he took the unusual step of announcing his dissent from the bench. His angriest dissent came, without doubt, in 2000, in the case of Bush v. Gore, which effectively ended the presidential race in favor of George W. Bush. "Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year's presidential election," he wrote, "the identity of the loser is clear. It is the nation's confidence in the judge as impartial guardian of the rule of law."

In 1992, he played a pivotal role in the court's reconsideration of its landmark 1973 abortion ruling, Roe v. Wade. The court was split into three separate factions: four justices to reverse Roe outright, three to uphold its core but allow more regulation by the states, and two, including Stevens and Harry Blackmun, to uphold Roe entirely. Upon receiving the draft of the three middle-ground justices, Stevens suggested a reorganization of their opinion so that he and Blackmun, the author of Roe, could join most of it. That way, he noted, there would be a single opinion that was supported by a court majority of five. The three quickly agreed, and the opinion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey became the new law of the land.

In his 2010 National Public Radio interview, Stevens said that in all of his years on the court, he really had just one regret: his 1976 vote to revive the death penalty by upholding a Texas death penalty statute. He said that, at the time, the court had adopted many rules to limit the death penalty to a narrow category of offenders and to prevent what he called "loading the dice" for the prosecution, but, over time, those limiting rules were abandoned. In his later years, he opposed most death sentences, winning rare but important victories, as when he wrote the court's opinion striking down capital punishment for the mentally retarded.

He maintained he was undecided about retiring, but in late June of 2010, his lengthy oral dissent in the campaign finance case was marred by verbal flubs. He was so distressed by his performance that he sought a complete checkup by his doctor. There was nothing wrong, but, not long thereafter, at age 90, he announced his retirement.

In the years afterward, he continued to be both physically and intellectually active, playing tennis and golf, and writing and speaking about the court and its work. When he thought the court in error, he gave critiques which were always pointed, literate, and respectful -- the very qualities that made him such a revered figure in the law.

Bio by: Glendora

Inscription

LIEUTENANT COMMANDER

UNITED STATES NAVY

Family Members

Advertisement

See more Stevens memorials in:

Explore more

Sponsored by Ancestry

Advertisement